In 2015, my friend Ben declared that he “doesn’t trust anyone who changes their hairstyle often.” His reason was that “it feels like they’re running from one personality to the next.” In short, he cooked. It’s a provocation that would haunt me for years, leading me to become skeptical of anyone with an ever-changing flow. However, upon reflection, I realized that I am implicated by this rule. According to Ben’s doctrine, it would appear that I am an untrustworthy hypocrite as I have changed my hair every year for the past five years.

Even though I am interested in aesthetics and presentation, the changes I have made to my hair have typically been driven by circumstance. My Fresh Prince-coded flat top in Singapore was groomed out of a dearth of Black barbers in the country, the messy mop that followed was sported when I couldn’t access a barbershop in the midst of the pandemic.

Last summer, when occupying a rare rush of intentionality, I decided to dye my hair for the first time. I wanted to rock a Frank-Ocean-dusty-pink fade and saved a reference photo on my phone to show my barber, Marshall. In his shop, Marshall explained that he would first bleach my hair blonde and then blend in the pink dye to achieve my desired hue. This made sense to me. I sat in the shop chair as he painted the bleach into my curls and then moved to the dryer chair to blast the bleach in. I emerged a Moses-Sumney-blonde. To test the shade of pink, Marshall dabbed a tiny bit of the pink dye to the upper right of my line-up and, together, we watched as the new colour set in.

Unfortunately, to my disappointment, the pink was more Barbie pink than the pale pink I wanted. My barber presented me with two options: I could either continue to dye my whole head a shade of pink I didn’t want or I could re-bleach the pink blot in the corner of the scalp blonde to match the rest of my hair. Neither sounded optimal, both felt like resignation. I stared at myself in the mirror and, on a whim, decided to carve my own path, adding and then circling a third ‘all the above’ option to the two that Marshall presented. Rather than dyeing my entire head pink or dyeing it all blonde, I decided to keep the “test” dab in and asked my barber to make the blot more pronounced. I wanted it to look like a blood stain. A head wound. I liked the way it looked and apparently, others did too.

A summer later, by way of manifestation, my fictional head trauma yielded a real one. It turns out that a year of bleach was not the best for the scalp. I began to wake up with blood stains in my durag. The crown of my head began to itch and scab. One night, I left blood on a lover's pillow. Something had to be done. And so, as my scalp shedded, so did the ‘blonde Brendon.’ I ceased the dye job to return to an earlier era: a tried and true fade. I liked the way it looked and apparently, others did too.

We’ve been culturally conditioned to think of our lives in “eras.” Change, be it cosmetic or skin-deep, is applauded with the assumption that with it comes growth. We watch as pop stars change their appearance as they leap to a new sonic chapter. When we fail to glow up we call it a “flop era” and when we return to the streets with revenge bodies and hot fits we label it as our “villain era.”

This episodic splicing of life’s events, major and minor, is useful. It allows us to easily digest and recall experiences in clean, concise chapters. Our self-narration gives us a degree of control in the wake of change. But for whatever reason, these shifts are largely tied to a transformation in image, as if to suggest that by changing ourselves internally we must also signify a change externally.

A month ago, Beyoncé turned 42. I digested materials that highlighted her success over the decades and her gargantuan impact on popular culture. Her Destiny’s Child era. Her Austin Powers era. Her On The Run era. Now, she is in her Renaissance era. But, despite this immense change and the success garnered from these calculated shifts, Beyoncé has always remained one thing: blonde.

Taylor Swift is another artist with numerous transitions, most predominantly across genres as she migrates from country to pop to folk. Her record-breaking tour celebrates this with the name ‘Eras’ and yet, similar to Beyoncé, she hasn’t deviated from her blonde hair. If you look across Swift’s album artwork, you will find similar features: blonde hair, and red lipstick on a mouth that’s slightly agape.

The largest and most successful brands in the world offer this consistency. Both of the aforementioned artists are amoung the most popular musicians of our time. Both are miraculous shape shifters who have persisted in the increasingly fickle attention economy of music. Yet, they’ve stayed true to a couple of key elements of their brand that have helped their fan base find stability and comfort.

A Big Mac tastes the same in New York as it does in Teipei. Around the world, Soho House provides the same signature shitty service. When the beverage brand Tropicana removed its most distinguishable element from its packaging, the iconic straw in orange, it lost $30 million in two months because consumers couldn’t find the product on the shelves. With these case studies in mind, why is there so much pressure for continuous reinvention and transformation?

One of the best arguments against eras and for consistency comes from fashion philosopher Rian Phin. In a TikTok, she advocates for a cultural regrounding in the definition of personal style, one that is rooted in aesthetic regularity:

“I disagree with the way that most people construct the idea of ‘personal style’ online. I don’t think there is enough emphasis on the ‘personal’ aspect of personal style. ‘Personal’ meaning your humanity and identity.”

Phin continues, elevating Brenda Hashtag as a prime example of someone who adheres to a personal style. Hashtag is the Berlin-based fashion editor of 032c, known for her envy-inducing black and white wardrobe of Ann Demeulemeester and Rick Owens.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Phin advocates that Hashtag “has a strong commitment to only wearing black and white… It is this demonstration, this massive exercise of discipline that we usually don't see from other people especially when they get dressed to relentlessly wear black and white. What you like is that she has something that most people don’t: a really strong expression of her discipline.”

This adherence to a personal philosophy that informs your aesthetic is connected to Ben’s concern about those who change their hair frequently. To both Phin and Ben, fragmented aesthetic choices signal a lack of self-awareness.

For those in the New York area, I am reading with some exceptional writers on Thursday, October 26th at Mood Ring. You can RSVP here for more details.

But what happens when you want to separate yourself from an outdated understanding? What happens when you intentionally wish to shed the expectations your community has attached to you? With society’s flawed attribution of how you feel to how you look, the quickest way to do this is by burning your current image to the ground.

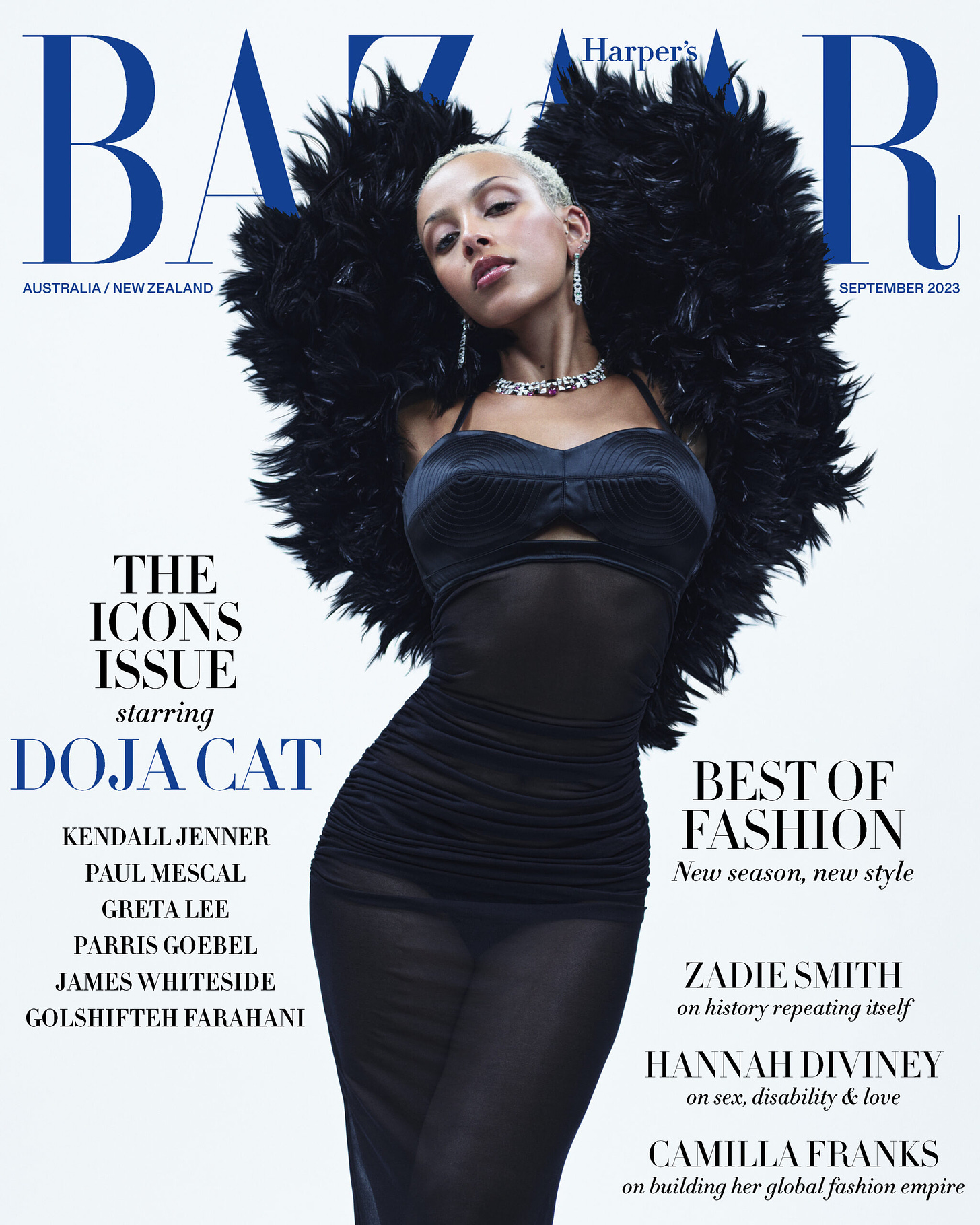

Doja Cat, with her recent rejection of her past image, understands this. Over the last few months, we’ve witnessed Doja’s outward condemnation of her previous projects as she cites them as ‘cash grabs.’ We’ve watched her trash-talking her fans, causing her to lose half a million followers on Instagram. Most reported on, however, was her physical transformation: her weight loss, her new dark punk makeup and occult aesthetic, and the shaving of her head into a short blonde fade. It appeared it was the summer Doja turned blonde, too.

With these changes, one can assume that she felt a new corporeality. A relief as she became untied to a past comprehension. Doja unlocked the freedom to transition outside the confinements of her ascribed genre and used it to draw attention to a more rap-heavy, tightly packaged sound on her fourth album Scarlet. With the success of her previous album, Doja reached a new career peak, equipped with a Billboard 100 number one and a GRAMMY Album of The Year nomination. She ushered in collaborations with industry juggernauts like Ariana Grande and the Weekend and a collection of copycats determined to replicate the success she forged straddling pop and rap.

On Scarlet, the new Doja is unbound. Unconcerned with respectability and fan service, her lyrics delve into her preoccupation with rejecting commercial expectations in favour of artistic expression. Whether this is a performed priority or an authentic one is to be determined but what is clear is that this Doja remains just as methodical in her music-making as she is in her image construction. The only songwriter credited across Doja Cat’s album is Doja Cat. As one of the most skilled lyrical technicians in the industry, her shape-shifting flow patterns, which can morph from a valley girl affect to rage screaming, are more akin to Eminem and Missy Elliott than her raptress predecessors Nicki Minaj and Cardi B. To me, Eminem and Missy are the most relevant comparisons for Doja given their application of ‘humour' in aesthetics, sound and politics. All three flirt with an element of play that simultaneously trolls industry standards while shifting across genres, beyond eras. Agora Hills has been on repeat in my house since the album release, a perfect score as we enter the ‘lover girl era’ for cuffing season.

The contrast between Doja Cat’s transformation and others’ refusal to deviate from a governing aesthetic reveals that there is no perfect formula. Personal style begins with self-awareness and your expression of self is allowed to be flexible, fluid, and firm. When done correctly, it’s less “running from one personality to the next” and maybe more “running towards yourself.” When done correctly, it should feel less like a rebrand and more like a return. That’s how I like to think about it and apparently, others do too.