welcome to strong feelings! Essays by writers we love, in which they share their most impassioned opinions on a given subject. If you love our usual advice column — don’t worry it’s not going anywhere. This month for strong feelings, writer and author of the LOOSEY newsletter, Brendon Holder, unpacks our culture’s obsession with the aesthetics of sadness.

In the closing stanzas of “All-American Bitch”, the intro track off Olivia Rodrigo’s sophomore album GUTS, she layers descriptions of what it means to be “all-American” today. Her muse is “grateful all the time.” She’s “sexy.” She’s “kind.” But most importantly, she sings in her final lyrics on the song, she’s “pretty when [she] cries.” Rodrigo offers no further support as to why this final attribute is as essential as the aforementioned qualities but, at once, I understand.

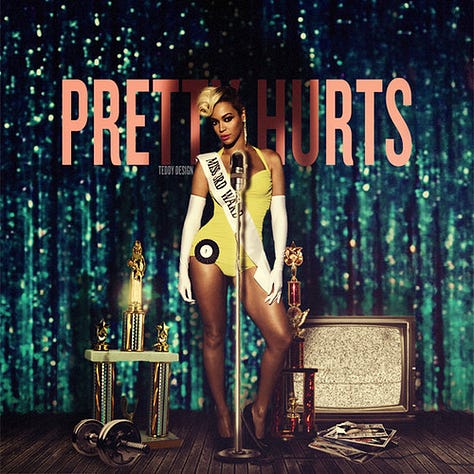

By emphasizing the importance of beauty whilst in a state of misery, Rodrigo nods to our culture's obsession with maintaining aesthetic control in the midst of internal unraveling. And she’s not alone in this observation. Rodrigo draws from a lineage of artists that juxtapose prettiness and pain, ironically or not. The artwork for Billie Eilish’s Happier Than Ever album shows the singer looking somewhere we cannot see, a single tear on her face. Even the Queen has weighed in on this phenomenon: Beyoncé’s “Pretty Hurts” posits that pain is an essential input for beauty, employing motifs of pageants and beauty queens against a tireless strain to “be happy.” And let’s not forget the headmaster of the #sadgirl boarding school — Lana Del Rey — who has made a career off of touting the beauty nestled within emotional fragility. Most famously, on “Pretty When You Cry”, the singer-songwriter suggests that her sadness is inherent to her beauty, recodifying her pain as a virtue. All this is to say: We’ve been conditioned to more readily accept mental strife when it’s packaged beautifully.

The chatter around mental health has shifted over the past few years to loud, virtuous proclamations around the collective need for therapy. We now exist in a world where therapy isn’t hidden, it’s celebrated, with ‘therapy-speak’ making its way into our cultural lexicon and becoming ever more commercialized. Jonah Hill produces a movie devoted to his therapist only to weaponize what he thinks he’s learned against his partner. Couples therapy has now entered our weekly rotation of reality television. Heck, even Barbie is depressed, plagued by thoughts of death. But as our collective awareness of therapy practices grows, why are we still so concerned with making it look good?

About a year ago, I switched to a new therapist who preferred in-person sessions over virtual. As someone who had begun therapy during the pandemic, I was accustomed to receiving treatment behind a screen where there was an unspoken acceptance of lower standards of physical presentation. With the shift to in-person, I noticed a change in my behavior: I wanted to look hot as fuck for my therapist. In fact, I’ve looked better in therapy than I have on first dates, job interviews, and my own birthday. To prepare for these sessions, I focused on presenting an image of a person at their most actualized. Maybe to contrast with the fact that I was about to lay bare parts of myself that really weren’t. And what says ‘actualization’ more than a freshly-shaved face paired with archival vintage sweaters, trendy trousers, and a jawline sharply gua sha’d with rose water?

I promise that this is not due to a deep-seated desire for my therapist. It has everything to do with my own misconceptions surrounding beauty and mental health. In addition to using my looks as a crutch in vulnerable situations, I came to realize that I was deluded enough to think that my focus on my image was for the benefit of my therapist. By presenting an unblemished version of myself, it’s as if I thought that I was helping my therapist do their job more efficiently. Allowing them to more quickly deduce that my presentation was not a driver of my issues so they could wield their therapeutic scalpel and probe at other signals of distress. But of course, there is no way to test this theory. My current is professional enough to never comment on how I look and, instead, launches right into how I’m feeling, my actions and my beliefs.

When I interrogate this behavior, it becomes clear that I, like the culture I critique, am capable of possessing an antiquated view of mental illness. A view that suggests that if I aestheticize my misery, my feelings will be taken more seriously and I will, in turn, be happier. But, in hindsight, I have seen too many Cate Blanchett movies (Notes on a Scandal, Blue Jasmine, Tár) to attribute ‘looking attractive’ and ‘dressing good’ to being impervious to woe. Trust me, there is no one who knows what a french tuck is and has all of their marbles.

Still, the concept of being pretty when you cry continues to permeate culture. “Crying Girl” makeup tutorials trend on TikTok while editorialized tears appear in glossy fashion magazines. In a vibrant spread for High Snobiety, Beauty Editor Alexandra Pully insightfully notes that “a decade ago, makeup was used to conceal the effects of a sob session or a late night out. Now, young people are wearing unkempt eyeliner and grungy eyeshadow as badges of vulnerability, signaling to the rest of their peers.” I wonder if the catalysts of the two seemingly opposing makeup trends are even that different. Much like the way I presented myself in therapy, both trends circle a desire to control.

But not every community has the luxury of vulnerable, albeit beautiful, emotionality. In 2017, to combat the stereotype of hardened, unemotional Black men, artist Quil Lemons photographed a series of Black subjects with streams of glitter flowing from their face, almost like tears, in a project called GLITTERBOY. I recall witnessing the portraits at the Aperture Foundation and feeling exposed by Lemons’ ability to capture the spectrum of emotions that I was capable of feeling but rarely saw represented. In this case, the makeup revealed rather than concealed because it challenged a prevailing societal belief about the subjects. Lemons captures this sentiment when explaining his guardrails for the project to Allure, "I personally will not shoot someone in my GLITTERBOY makeup unless they're a young Black man or a young man of color… There's a privilege that comes along with being white when it comes to self-expression, sexuality, and fluidity. Black men really don't have that. They really are policed with what they can and cannot do, so this project was to bring light to boys that get overlooked." While his work garnered some vitriol in comments, to me, the online quibble had less to do with Black men wearing glitter and more to do with the provocation in the beginning of Lemons’ text: that Black men could be allowed to be real.

On GUTS’s penultimate song, Rodrigo returns to society’s troubled understanding of beauty and mental health. In a defeated delivery, she sings that even if ‘you fix thе things you hated… you'd still feel so insecure.’ Again, this is not a revelation, her lyrics in conversation with TLC’s Unpretty released over two decades prior (‘My outsides are cool / My insides are blue’). Rodrigo continues, suggesting that not only does the race towards beauty fail to rescue her from mental hardships, it’s the source of it: ‘When pretty isn't pretty enough, what do you do? And everybody's keepin' it up, so you think it's you.’

For Rodrigo, for TLC, for Barbie and for all of us, being pretty when you cry may be a vibe, but being preoccupied with our exteriors doesn’t give us room for the right kind of interior work. Like a carousel, the fantasy ride towards beauty can be fleeting and fun but, if you stay on for too long, you’ll only end up feeling more sick.