Is Feeling Sexy a Human Right?

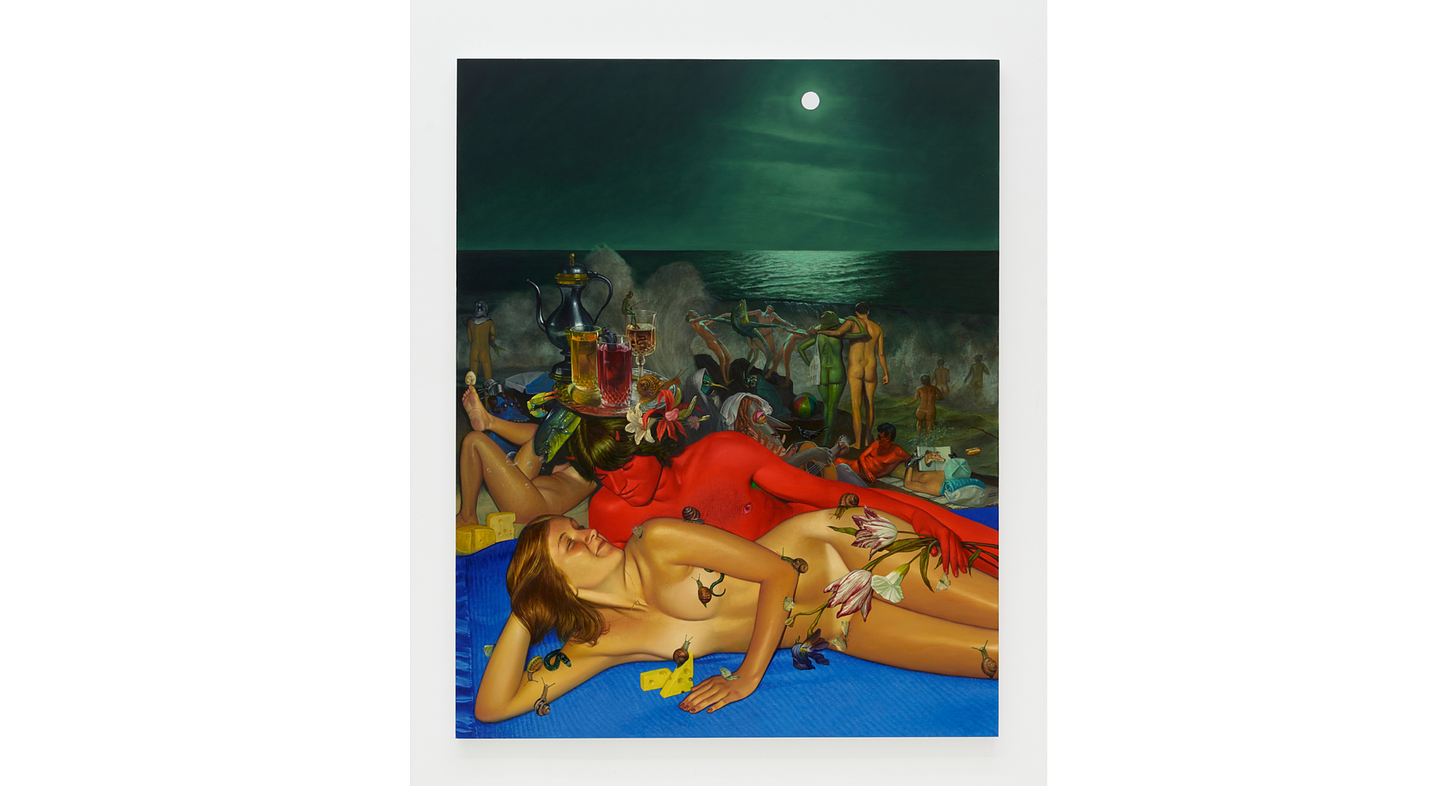

all fours, cruising, the substance, clairo and stranger by the lake

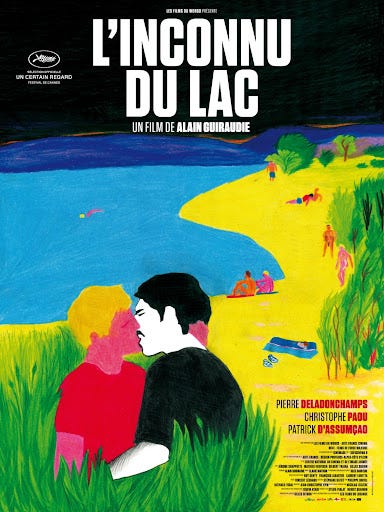

There are three movie posters in my apartment. The first poster is framed in metal and portrays Uma Thurman in a yellow and black leather tracksuit, gripping a katana as The Bride in Kill Bill: Volume 1. It has followed me from apartment to apartment and hangs across from my sink. The second two are more recent purchases, obtained through the Posteritati acquisition team, and have black wooden rims. The French promotional poster for the 1997 cult anime Perfect Blue hangs in my living room while a massive, cinema-window-sized poster of the 2013 thriller L'Inconnu du Lac, known to English-speaking audiences as Stranger by The Lake, hangs in my bedroom.

The final film in the trio, whose poster took over a year to locate and mount, is about a young man consumed by his desire. Set on a nude beach in France’s Provence, Franck witnesses a man drown another man in the lake, popular for cruising (not the kind that involves boats). His attraction to the murderer (Michel) overpowers his fear, and soon, against his friend’s advice, he develops an intimate relationship with the titular stranger by the lake, meeting him with an eager frequency on the rocky sands of the beach or the grassy fields just beyond it. As days pass, the police investigate the lake and question Franck. Although Franck and Michel’s relationship remains mostly physical, their relations begin to feel more intimate to Franck, and blinded by the possibility of love and dickmatized beyond reason, he barrels towards oblivion.

The movie closes with Franck running away from Michel as night falls over the lake. Franck hides in the darkness of the woods, seemingly safe from the stranger, and then, surprisingly calls out his name. First, timidly, “Michel?” And then, pleadingly, “Michel!” The screen cuts to black, the sound blooming with the snaps of twigs, chirps of insects, and Franck’s increasingly fevered calls. Franck waits for something to happen but we aren’t privy to just what.

Kill Bill, Perfect Blue, and Stranger by the Lake are representative of my taste when it comes to film, fiction, and fact. These stories are in conversation with one another, all pointing to themes that interest me like the spectacle of uncorked desire, an ambition-fueled death drive, stylish visual language, and a dab of toxic obsession. Every morning, as I get ready, the posters subtly ask me how far will I go for the things I desire and, ultimately, at what cost?

This summer, I went to Provincetown, Massachusetts to celebrate a friend’s birthday. I had been to Cape Cod a couple of times, always to attend a restorative weekend at a friend’s place in Falmouth to close the summer. I had taken a ferry across to Martha’s Vineyard for a day trip and ate seafood towers, pretending I was an Obama. But I had never been to Provincetown. Prior to moving to the U.S., my only knowledge of The Cape came from images of the Kennedys and a handful of Vampire Weekend songs. When I first heard Ezra Koening sing “Fuck the bears out in Provincetown. Heed my words and take flight,” in Walcott, I assumed ‘the bears’ was an American sports team. After visiting P-Town, I know better.

P-Town is idyllic, an American postcard in the flesh. We biked everywhere and took buttery bites of lobster rolls and I remembered how to sleep in again. Then, one day, we went to the beach – a nude-friendly one. Now, I don’t know what this says about me but four to five people – some of them who weren’t even on the trip, voice noting me from afar – felt the need to warn me (and only me in particular!) that the journey to the beach would be a ‘trek.’ Warning me that this journey involved a lengthy bike ride and (!!!) a hike. Didn’t these people know that I went to Zoo Camp as a child? That I was raised on Richard Hatch-era of Survivor and the great outdoors do not scare me one bit? This only galvanized me as I packed my ‘trekking gear’ – a tote bag stuffed with Portnoy’s Complaint by Philip Roth, Supergoop Unseen sunscreen, a film camera that only works when I slap it, and other essentials like Doritos – and barrelled down the highway with the troupe.

Once we got to the marshes, still damp from the retreating tide, I clocked why my friends warned me. All around us was dirt and we had to pass through it to reach the beach. I glanced around for a cobbled walkway and realized that there was only one way to go: through the murky waters. The muck reached past my ankles as I clamped across the soot, reminded of that swamp in Lord of The Rings with the dead bodies floating in it. And then, when the water began to lap against my thighs, I distracted myself by picturing the beautiful ocean scenes in Beyoncé’s BLACK IS KING where she migrates through the water. I didn’t complain once, determined to beat the only child allegations. Ask anyone. Ask everyone.

I quickly kicked back on my sandals when we arrived at the beach, the sand becoming hot coals against the tender soles of my feet. As we skipped around to find a spot to lay out I was surprised at how many people were clothed. I’m not, like, an exhibitionist and have only been to a ‘nude beach’ once but I thought it was kind of an all or nothing kind-of-thing. The beach was about 30% naked and the naked people almost seemed like they wanted to be seen naked which made me kind of not want to see them naked if that makes sense. Because of this, I decided to keep my swimsuit on. Or “behind a paywall,” as I told Nic.

As we shuffled along the beach, I locked eyes with a gentleman, probably my age, who was performatively holding a copy of Gabriel Smith’s Brat. A dog whistle. At first, I noticed the novel, finishing it a few weeks prior, and then I noticed the hand and bicep attached to the book. And then I noticed him. All of him. He smiled, and I smiled back. He seemed friendly.

After thirty or so minutes of laying out, I noticed something else. Drones of people heading to a grassy bit behind us, an upward slope of sand and green sprouts. They would go in, sometimes alone and other times with others, and emerge, skipping past our beach blankets, somehow happier, with a newfound buoyancy in their step. My eyes clawed at the grassy cliffs and I thought of the boy with the book.

“What’s back there?” I asked Jordan, the birthday boy, and my Provincetown sherpa. I could probably make an educated guess, figuring it had something to do with desire but sometimes it's more amusing to be told things you already know the answer to. To have it come out of someone else's mouth, rather than your own, like a ventriloquist.

“The dunes,” he answered. And I understood. I removed the Philip Roth from my bag and held it out performatively – a dog whistle – and, like Franck, waited for something to happen.

The past few months have felt like this, wrenched with stories that observe desire from all angles. A couple of days ago, I finished Miranda July’s All Fours, an interior work of autofiction that follows the narrator – a mother/wife/artist of considerable fame – on a solo road trip to New York from California for her fourty-fifth birthday. As she confronts this new age, she considers how the metrics of her own her desirability have changed. How has she taken advantage of her desirability? How has she not? And, most importantly, is it too late? I read the novel skeptically, traditionally a bit cooler to ‘plotless’ fiction, but ultimately was won over by July’s prose and honesty. Below is an excerpt of one of the narrator's many masturbatory fantasies:

“I was too old for him. This was my first experience of being too old. I had not always gotten exactly what I had wanted – men had been unwilling to leave their wives for me or to do more than flirt – but even in these humbling cases I hadn’t questioned my right to feel desire. Now suddenly my lust was uncouth, inappropriate. I was powerful and interesting, perhaps funny and unique; I took him seriously in a way he wasn’t used to – but he was not jerking off to me. Just a few years earlier, at forty or forty-two, I would have been a contender, but now it was too late.”

Later, she returns to this desirability anxiety but this time her preoccupation is aimed outward, at a bodily object to project her urges onto:

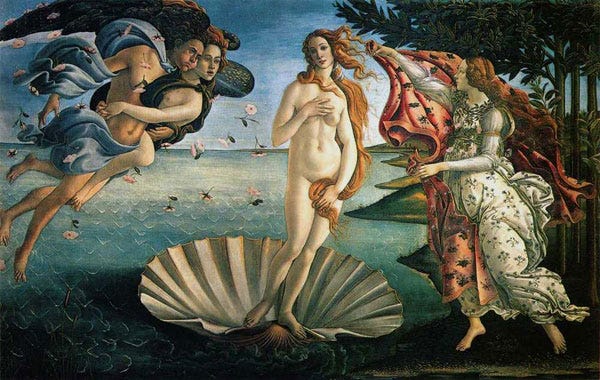

“But to be clear, I had not, at any age, desired a specific male body in the way I did now. While all my boyfriends and crushes had been reasonably good-looking, my attraction hovered up near their face, where they kept their talent and power. Lusting for the whole length of a person, head to toe, was what body-rooted fuckers did… Now, for the first time, I understood what the fuss was about. How something beautiful could strike your heart, move you, bring you down on your knees and then, somewhat perversely, you wanted to fuck that pure, beautiful thing. Sex was a way to have it, to not just look at it but to be with it I suddenly understood all of classical art. The endless carved nudes, Venus in her shell, David.”

Miranda!!! Every decision the narrator makes is driven by an ambition to preserve her independence and her right to sex and, in the process, she blows up her life to build a new one. That is her cost. To limit the novel to its sex would be reductive but to gut it of its sexuality would be to obliterate the work completely. I am most impressed by the vulnerability of July’s narration, a warped facsimile of her own life. She longs for love and intimacy. At times, it’s embarrassing but not in a way that defiles her character. Her desire is not subservient in the way that Annie Ernaux writes in the brilliant Simple Passion but a necessary input to her personhood. As vital as her beating heart. Suddenly, Franck’s calls for Michel at the end of Stranger By The Lake seem less like feeble acts of desperation and more like carnal declarations of what he is owed. Just last week, All Fours was longlisted for the National Book Award.

The whole ‘desire to be desired’ thing of All Fours is in dialogue with Clairo’s sultry summer single Sexy to Someone, off of her third studio album Charm. I absolutely love the album and enjoyed witnessing it live last week at her residency in New York. In the caverns of Webster Hall, the air skunked of weed and sour wine, the singer slinked around a stage that looked like an intimate recording studio, designed by Imogene of Charli xcx BRAT roll-out fame. As a crowd, we felt like voyeurs.

Before singing the penultimate song, she raised the mic playfully to her lips and purred the following demand: “Can you boo if you find me sexy?” Under her command, the crowd lost it.

Sexy to somebody, it would help me out

Oh, I need a reason to get out of the house

And it's just a little thing I can't live without

Clairo’s platform isn’t too different from July’s. In fact, they could run on the same ballot under the campaign that feeling sexy and desired is a human right.

But again, I ask: at what cost?

We’ve seen the horrors of filler migration on TikTok. Botched BBLs and ugly veneers are everywhere. Thirst traps weaponized in revenge porn. If our desirability cannot be extracted from external pressures (capitalism, the patriarchy, yadda yadda, etc), are our desires actually our own? And if these external pressures are inherently toxic, does that mean that any method to preserve desirability will eventually poison us?

Carolie Fargeat’s new film, The Substance, seeks to answer these questions directly.

I saw The Substance on opening night with Kurt, in a packed movie theater that served Pepsi, not Coke, and didn’t allow you to reserve seats in advance. Still, I admired the charm of the old-school theater. Its guests are typically casual cinephiles or something close to it and it usually weeds out the chatty AMC A-Lister types (hey, some of my best friends are AMC A-Listers) who see films to satisfy a value equation rather than out of true interest in the specific film at hand.

I went into The Substance without much knowledge, having skimmed through Demi Moore and Michelle Yeoh’s conversation in Interview and believing that it was about some age-preservation drug that had some questionable side effects. Without spoiling too much (I know I spoiled tf out of Stranger on the Lake lol), the film follows Elisabeth Sparkle (Demi Moore), the host of a workout show who gets canned at 50 for being ‘too old’ by a pompous network exec (Dennis Quaid). She is saddened and confused by this sudden exit, seemingly unaware of the invisible metrics the network has used to deem her invaluable other than her age. She is told that when you’re fifty, everything just ends by the network exec, who is named Harvey for fast characterization. As for Sparkle’s (flat) characterization, we are left with the lore of Moore’s career to extrapolate and fill in the gaps.

In reaction to being fired, Sparkle starts taking ‘the substance,’ a chartreuse injectable that allows you to birth a younger, better, more desirable version of yourself to take your place every other week. It’s giving Severance but instead of swapping between a work-self and a life-self, it’s across desirability metrics. Sparkle’s younger self, named Sue, is portrayed by Marget Qualley. After a successful audition, Sue steps in to replace Elisabeth on the network and hosts a rebranded workout program called Pump It Up. And so, the duo begins to trade weeks from one another with Sue stealing time, jeopardizing the experiment and the safety of both women. This tension sends the audience through stylish scenes of grotesque body horror, satirical fights, and more guts and blood than a Julia Ducournau film. The whole thing felt wackadoodle (official film term). There isn’t thaaaat much dialogue from the leads to develop the characters beyond their desires. Instead, it’s a continuous build of absurdity that demands your submission throughout its Cannes Festival-winning screenplay.

For Sparkle, her desirability is less about feeling sexually validated and more about survival. In the world Fargeat creates, not much different from our own, the women understand that their livelihood and worthiness is predicated on their ability to maintain desirability. If men think they are hot, they are valuable. And if they are valuable, they can live a life of respect. We aren’t offered much to know why Sparkle continues with the substance for as long as she does but it feels like she’s clinging onto something she’s built. Like the narrator of All Fours, her desirability, and all it connects to, is something she feels like she’s not only owed but earned.

After finishing the film, Kurt and I humoured ourselves by naming which friends would take the substance in real life. At first, the idea of taking the substance felt idioic but then, as the days rolled on, I started to think otherwise.

In retrospect, a better question would have been: what substances already exist, over the counter and through other streams, to enhance desirability? And, with the evidence from the stories above, should anyone feel ashamed for taking them?

In the end, desirability is less of a human right and more of a universal experience. The cost of being desired or undesired is the same. On either end of the spectrum, you pay with your humanity.

LOOSEY is a bi-weekly newsletter about culture, technology, and the way we live. If this is something you like, consider subscribing and sharing. Let’s be friends on Instagram.

Compelled by your writing always! Really interested in how these themes interact on the opposite end of the spectrum with incel culture… when desirability is withheld from someone and they have no “substance” to turn to besides anger. “The Right to Sex” by Amia Srinivasan speaks to this, but it’s been years since I’ve read it so perhaps a reread is in order.

When you write “miranda!!!” unfortunately it’s Steve’s voices I’m hearing in my head