Like many of us, I have been chewing on the completion of HBO’s Succession for the past week and readying myself for a Sunday evening spent without Siobahn Roy’s power suits. It’s not surprising that I’ll miss the characters the most, a bleak troupe of anti-heroes who are too blinded by their own wants to see that they are the problem. The antagonists that garnish Jesse Armstrong’s show are delicately developed. So squarely terrible yet expertly well-rounded that you find yourself turning them over with every passing episode, squinting to locate a modicum of compassion lodged beneath their mountainous cruelty. In real life, I would not care to be in the same room as these people, and yet, each Sunday on the screen, I found myself rooting for the corrupt slew of morally impoverished, capitalist murderer-cucks. Analogous to the fickle moral compass of the Roys, I found it nearly impossible to commit to a ‘favourite’ from the doomed family. Instead, as the series progressed and the Roy children’s mental faculties splintered, I gravitated towards the supporting cast, warmed by their consistency and logic, although just as multifaceted and complicated. I will miss Nan Pierce’s brute stewardship that she insidiously cloaks under her southern charm. I will miss Caroline Collingwood’s selective and cruel vulnerability, an enigma of a mother whose absence seemed more justified each season. I will miss the magnetism of Stewy’s shit-eating grin, Gerri’s stoic unflappability and Matsson’s cute Acne sweaters. To be clear, these are all deplorable people. But, Logan daddy, I will miss them!

Throughout its five-year run, Succession became a cesspool for cultural criticism, spawning think piece after think piece on how the tenets of the drama and the structures that the characters operated in mirror our day-to-day realities. Most of the coverage points toward how the series navigates class, from the dissections of Tom Wambsgan and the tired discourse on quiet luxury. Although I believe class is an integral fabric of the show, I do not believe that it is the central propulsion or even related to its thesis. In short, I believe Succession could have been about blue-collar siblings battling over the ownership of their mother’s meatball sandwich shop in Staten Island and been just as effective.

The structure of class in Succession, and in real life, is a decoration rather than a driver. Instead, I believe Succession is a show about ‘the chase,’ the tireless pursuit to fill your vacancy with something external. We watch as the siblings squabble, debasing themselves and those who love them for the CEO title. Toward the end of the series, it became more apparent that the sibling’s desire for the title outweighed their ability to grasp reality. Their hasty decision to ditch their The Hundreds venture and bid to acquire Pierce Global Media. Their messy, unbalanced tactics to finalize then fuck and ultimately forage the GoJo deal. Their inability to see just how shit they were at business. By the end of it all, I began to question their actual motives for wanting to be CEO. Why would Shiv, the most liberal-leaning of the siblings with practically no business acumen, want to be head of a failing right-winged news organization? Is this something she’d actually enjoy? Why would Roman, someone who at one point was best positioned across both Logan and Matsson’s camps, fumble every opportunity he had to flex his leadership (on the mountain with Matsson, the investor conference presentation, the funeral speech, firing Joy and Gerri), and still be so convinced he should be CEO because his dad ‘said so?’ How could Kendall jump from initiative to initiative so quickly, eager to uphold an organization that he once publicly denounced? An organization that puts his family in harm's way and jeopardizes democracy? To me, their desires seemed deluded but perhaps most desire is. Desire is often never about the thing you wish to hold and is often a signal for what you’re missing in yourself. Within the CEO title, the siblings were ultimately chasing the acceptance they never received from their father, a gaping hole of lack that only grew bigger after his death. Their desires pointed to a lack that Waystar Royco could never fill but they were too blinded by the chase to realize.

When the pandemic separated me from someone I desired, I found myself listening to Caroline Polachek’s Pang. I don’t believe there is a contemporary musician that captures the yearning for something or someone out of reach so acutely as Polachek. Her buzzy So Hot You’re Hurting My Feelings fused the desperate crave for an out-of-reach lover with placid synths and electronic vocal harmonizations, making it a #PanDemiMoore breakout. When Caroline references love, she usually associates it with discomfort or pain. Polachek describes the moment Pang came to her, erupting from an “urgent kind of internal hunger… something very internal that kind of pricks you emotionally from the inside.” She revisits this sensation again on Ocean of Tears where she mournfully depicts the pulsating agony that lack can often incite:

“This is gonna be torture before it’s sublime / Does that make me crazy?

Oh my god, I wanna know what it feels like / Just an inch away from living the dream life / The only thing that’s separating you and me tonight is an ocean of tears.”

The motif of yearning and desire appears again, more prominently on her latest album Desire, I Want To Turn Into You, cleverly released on Valentine’s Day (and LOOSEY’s birthday, if you choose to celebrate). Her position is in the album’s name. By stating she wants to turn into her desire rather than be with her desire, Polachek signals her ambition for her lover to occupy her lack. In relation to the chase, this is a revealing vantage point to make music from as it correlates keen attraction for an external party with disappointment in one’s internal merits. She alludes to this transfusion of identity and her ambition to become her lover in my favourite song on the album, Blood and Butter:

“Look how I forget who I was before I was the way I am with you /… Let me dive through your face to the sweetest kind of pain / … Oh, I get closer than your new tattoo.”

Again, Polachek references the painful strain of yearning but, on this particular chorus, her desire veers into obsession with illustrations of her wanting to wear her lover's face to gain a deeper sense of intimacy. It’s beautiful, it’s crazed, it’s a bit Fatal Attraction but it works well in exemplifying the self-destructive tendency of the chase. It illustrates how anxious desire erodes the self in an effort to bring you closer to the thing you want while simultaneously destroying the ego through sublimation and humiliation. Returning to Succession, Polachek’s situation is not far off from the Roy siblings. Kendall, Roman and Siobhan have publicly demeaned themselves in an effort to be loved by their father. They’ve removed the ribs of their own personal values in order to contort and bend to the winds of Logan’s demands. Unfortunately, none of this brings them additional security or confidence. Lack can only attract lack.

It’s worth noting that on the album Polachek rarely sings about actually ‘getting’ what she desires. She never articulates scratching that itch. Instead, her microscope on the brutal yet exhilarating chase brings her closer to the edgelord Roman out of all of the Roy siblings. Like Roman, Caroline is all foreplay, no climax. What she wants is often behind a pane of translucent glass as she salivates with her nostrils pressed against it. Her pants fog the glass frame, preventing her from seeing her own reflection. She can only see what she desires. Out of breath, her contribution to her own spiral becomes clouded.

To zoom out of my own spiral, I often return to the water. The crashing waves of Barbados slapping my calves as I mount a surfboard. The questionably murky scent of the tides of Hanlan’s Point on Toronto Island. In the wells of the bathtub in my childhood home, invisible and submerged.

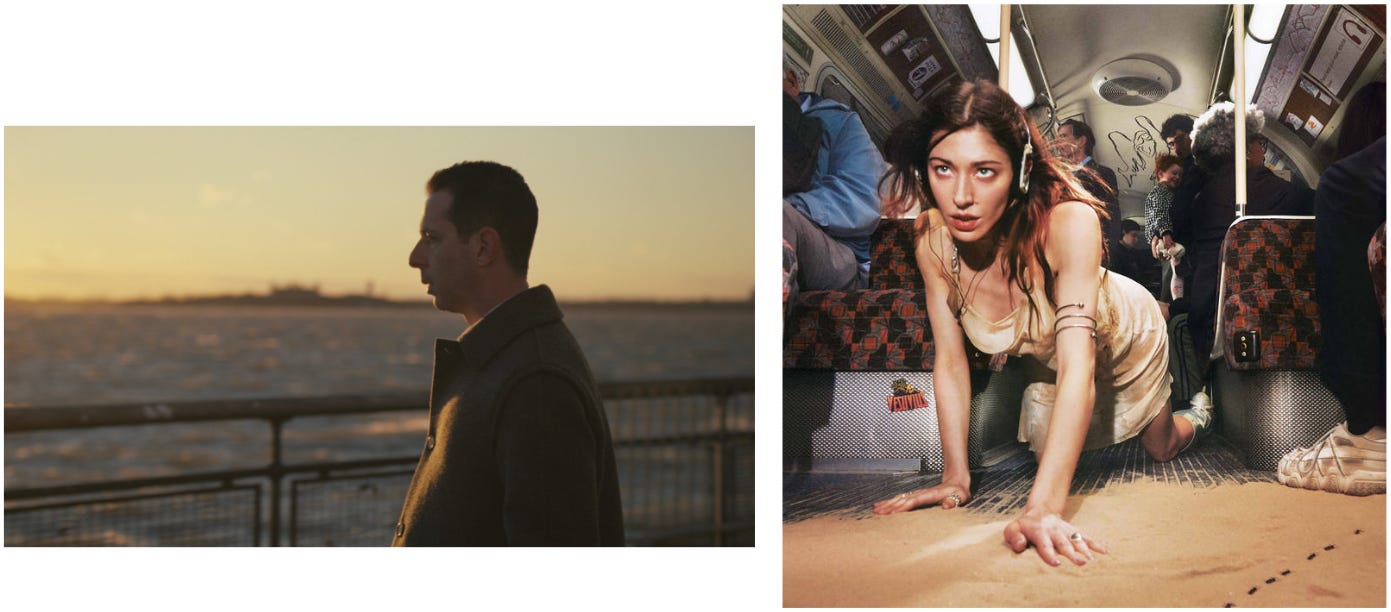

Both Succession and Desire, I Want To Turn Into You are alike in their employment of water as allegories. For Kendall Roy, open water has been used to represent the fragility of his morality and mental state. We see it first in season one, at Shiv and Tom’s wedding, after he attempts to take over the company from his father. Later that evening, in a ketamine and alcohol-laced stupor, Kendall drives his car over a cliff, drowning a waiter in the lake. It returns prominently in season three, when, again under the influence, Kendall nearly drowns himself in a swimming pool after drunkenly passing out face-down on a floatie. Finally, it bookends the series finale, beginning with Kendall playfully jumping into the Barbados sea after reconciling with his siblings to the final scene of the show, him desolate and defeated, staring out at the Hudson. It appears that he is about to take his own life but the viewer never finds out.

For Caroline, water is fortunately more uplifting, playing into the deserted island imagery she concocts on her album. The album’s cover spotlights Polachek on all fours in what appears to be a subway car, crawling towards something sandy we cannot see. Her mouth is agape, her eyes are zombified as if entranced by her desire. Her gaze mimics Kendall’s in the final scene of Succession: two pairs of retinas fully consumed by the oasis they’ve been chasing, only to find out that it was never theirs. It was just a mirage, their respective chases nothing but a trivial pursuit.