Somewhere between my second baguette of the morning and my first bowel movement of the day, I realized had been here before. As I entered the café’s bathroom, moth-bitten memories flowed in rosily. I recalled how the tiled stairs sharply descended towards the sink and the narrow corridor that led to le bain. Roughly a decade ago, I visited this exact café in Paris at random. It had been my first time in the city and I was visiting from Libson where I was on an “academic” exchange for the semester. At the time, I entered the establishment only to use the bathroom, offering the host a botched “Puis-je aller au toilette?” I was ignorant of the café’s historical significance at the time but I emerged relieved, with my elementary-level French validated.

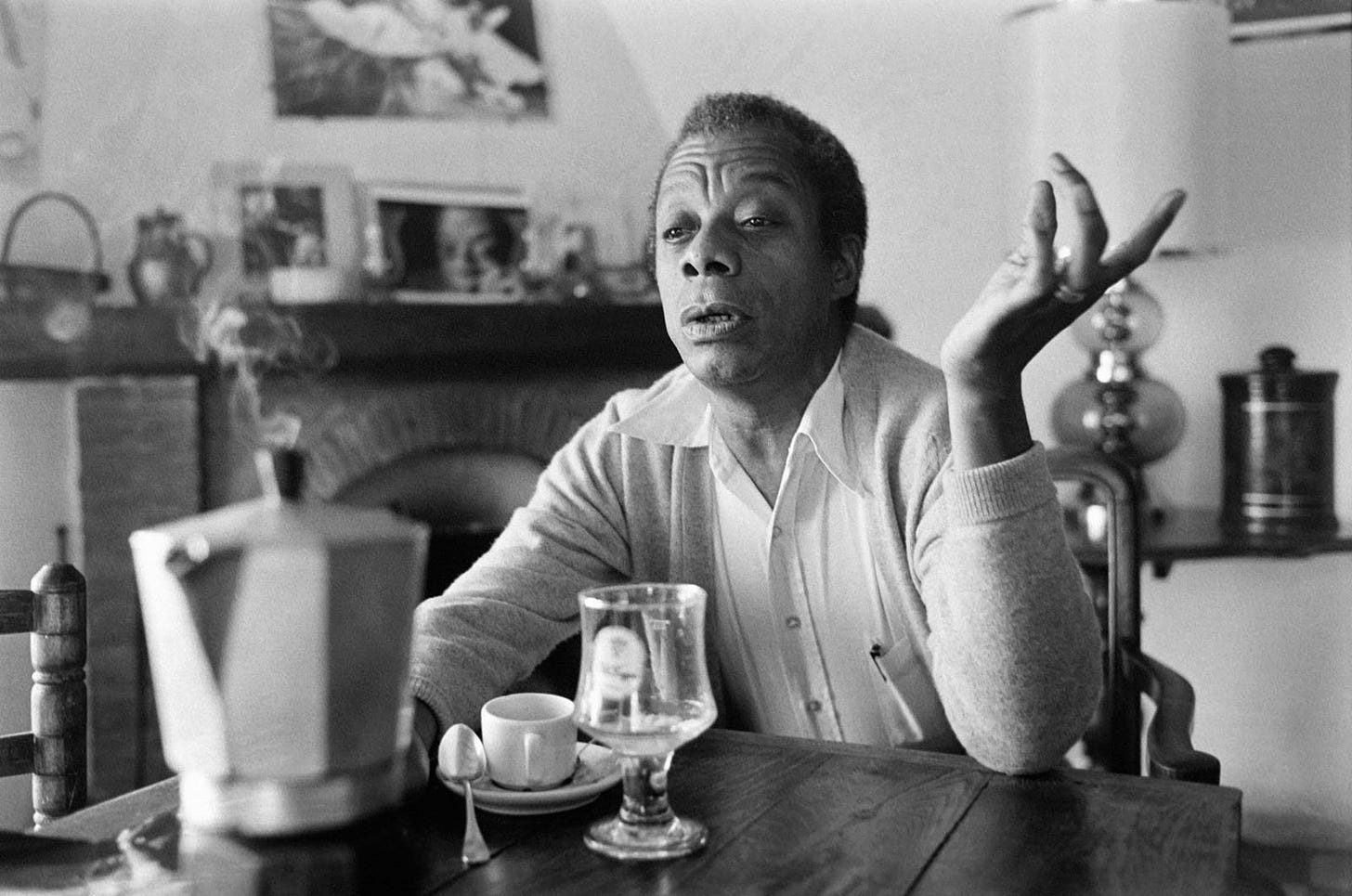

A few days ago, I went with a greater intention. Les Deux Magots is deemed to be the most famous ‘literary café’ in the world. Located in the sixth arrondissement of Paris, it was frequented by artists like Ernest Hemingway and Pablo Picasso, and later, James Baldwin. Soon after sitting down, I discovered that it is also a raging tourist trap, devoid of the charm I witnessed in Midnight in Paris. I wished to experience the glint of an older Paris, a Parisian past life, but that history was suppressed by renovation and capital interest. I came with a notebook and pen, ready to conjure whatever inspired Hemingway to write The Sun Also Rises at the historic café decades earlier. But, instead of a novel, I wrote this.

As I departed the café and traversed toward the Luxembourg Gardens, I discovered another uncanny coincidence. Directly across the street, less than forty metres away, was another café I had eaten at last summer with friends. It was disorienting to be met with so much familiarity in a short window of time, in a place that was vaguely foreign to me. This was my fourth time in Paris and yet, unconsciously, three of the four times I found myself returning to the same intersection, the same cafe. Pourqoui?

Upon visiting a new place, have you ever had the eerie suspicion that you’ve been there already? Relatedly, have you ever been introduced to someone and felt that you’ve already known them for a long time and somehow misplaced the memory of meeting them?

Have you ever met someone only to discover that you’ve unknowingly run into each other for the past decade, in the same places, perhaps slightly missing each other as you grazed past them at a Vietnamese restaurant seven years ago or attended the same concert five years ago or mindlessly matched with them on a dating app three years ago?

Some of these experiences can be chalked up to déjà vu, a false familiarity tied to a situation or person that you haven’t encountered before. As déjà vu is predicated on the impossibility of you meeting the person or visiting the place in the past, the most prevalent explanation is akin to a ‘brain fart.’ Neurologists have cataloged the phenomenon as a split awareness of two sequential processings. The first processing is experienced when you are distracted or not fully present, causing you to have an obstructed absorption of what is in front of you. When you finally get your wits, likely a split second later, the second rendering overrides the first, colliding into it. This causes you to feel like you’ve experienced it before because… well, you sort of have.

To me, this explanation has always felt limited. The feeling of déjà vu can be so overwhelming that it seems far too simple to pinpoint it to a minor mental spasm. It also doesn’t offer guidance on life’s odd synchronicities, like mine in Paris, where greater forces appear at work. The theory’s unwillingness to acknowledge that you may have unconsciously come across a person or place in the past positions it in opposition to my second set of questions that nudge towards a fusion of fact and fate.

I travelled across the ocean to see the Queen Beyoncé on her Renaissance World Tour. My friends convinced me that the ticket pricing was more favourable in Amsterdam than in New York so I obliged, persuading myself that it was the economic choice. Another ‘economic choice’ I made was to stay a few extra nights in Paris prior to meeting my friends in Amsterdam because who wants to go to Europe just for a weekend? And so, I planned a solo trip to Paris, a bottle episode if you will, before connecting with friends in the Netherlands. My plan for Paris entailed writing and reading. That is what I told myself when I booked the ticket, took the time off and packed the suitcase. That had been my intention but: man makes plans and Beyoncé laughs.

One night in Paris, I was eating dinner at a dimly lit bistro recommended to me by a friend. The dishes were a contemporary mix of French-Italian cuisine, greatly inspired by the Basque region. I rotated through the crowd pleasers: veal tartare, mezze pasta al dente and arancini while happily slurping on a blood-orange negroni spagliatto. A heat wave moved through Paris as I licked the condensation off the glass. As I enjoyed my last few bites, performatively reading Baldwin’s “The Black Boy Looks at the White Boy,” my waitress asked if I would be comfortable with someone sitting next to me. Acclimatized to the claustrophobic New York, I had no issues.

After a few moments, my dinner companion and I struck up a conversation and discovered a web of bizarre consistencies. Not only was he also visiting from New York, he also was a writer who had come to Paris to write. In his case, to attend a poetry workshop. Oddly enough, we both moved to New York within months of each other. The American poet was in the process of completing grad school and waited tables at a trendy, Italian restaurant in Brooklyn owned by a chef I admired. We bonded over balancing writing with other life matters and shared our subsequent plans for the summer. After giving me the deets on his restaurant’s secret menu, he grinned, “It’s likely that you’ve come in while I was working.” I smiled back but didn’t respond as I was certain I would have remembered his face. But then again, I had been eating at the same place in Paris over the course of a decade and had no idea until now. The city had been so full of freakish coincidences… How could I be sure of anything? The evening went on and we drank our red wines. I never finished the Baldwin essay.

Artists across mediums have attempted to decode the enigma that seemingly straddles coincidence and fate, where forces beyond our own capacity appear in control. In Past Lives, Celine Song’s debut film, in-yun is offered as a potential explanation. The romantic drama documents a relationship between two classmates, Nora and Hae Sung, whose friendship is severed when Nora immigrates to Canada at the age of twelve from South Korea. Decades later, the two reconnect in New York, which arouses feelings of nostalgia, lost love as well as a cycle of deep reflection on the choices they made (and didn’t make) that caused their lives to splinter.

Nora, portrayed by the criminally underutilized Greta Lee, describes in-yun as the Korean word for fate. She explains in-yun’s influence on relationships at a writers workshop later in the film as an adult:

“It’s an in-yun if two strangers even walk by each other in the street and their clothes accidentally brush because it means there must have been something between them in their past lives. If two people get married they say it’s because there have been 8,000 layers of in-yun over 8,000 lifetimes.”

At the point of reunion, both Nora and Hae Sung have separate, established lives: Nora - a playwright in New York - has married an American writer while Hae Sung - an engineer in South Korea - has an on and off again girlfriend who he is considering proposing to.

When Hae Sung visits Nora in New York after two decades of distance and fractured communication, the chemistry between the two is palpable beyond the screen. Greta Lee expertly illustrates Nora’s mental exploration of “what ifs” without saying a word. Correspondingly, Teo Yoo’s Hae Sung translates the feeling of yearning trapped by culture and distance that he can’t communicate to Nora without infringing on the boundaries of the American life she has built for herself. The tension is slow and suffocating. Like most complicated relationships, so much rests in the unsaid that it begins to take its own shape, feeling like another character. In the end, without explicitly acknowledging their harboured feelings, the two ‘make’ the non-decision to stay on their current path for this lifetime. During their departure, wrought with a pulsating, silent longing, Nora asks Hae Sung if he believes in in-yun. Up until this point, we only see her explain in-yun to an unimpressive American at a writers workshop who she ends up marrying. It feels redemptive, almost cosmic, that Hae Song not only believes in in-yun but suggests that they have another layer of life to live before they can really be together. It’s at this precise moment in the film that our hearts break in unison.

As someone who is frequently preoccupied with life’s peculiar consistencies, Past Lives punctured me in an unexpected way. This predisposition coupled with the similarities between Nora and my life - her parents immigrating to Canada, her career move from Toronto to New York, her being a writer - struck a nerve, forcing me to recontextualize the life I am living to consider who and what from this life was present in a past one. That said, it’s difficult for me to acknowledge Past Lives as a perfect love story. I question if Nora’s inaction towards Hae Sung later in life was truly out of a commitment to her partner and more out of a commitment to the life she built for herself in New York. I found the chemistry between her and her American partner uninspiring and was in disbelief that she found her true equal but recognized that her submission was one many immigrants make in an attempt to find a match in a cultural terrain that is vastly different from their origin. Regrettably, I identified with this compromise. Whether intentional or not, I found the love affair between Nora and Hae Song lopsided and sensed that the film only characterized Hae Song by his desire to chase Nora, with minimal effort to flesh him out as an individual. It was as though, since childhood, he walked around with a Nora-shaped hole in his heart. I found this upsetting but I suppose this was all part of Song’s design. If Song meant for the film to be a perfect love story, Nora and Hae Sung have ended up together. Although the conclusion of the film was melancholic, the overall outlook is optimistic. In-yun suggests that love is boundless and lives beyond our lifetime. Our connection with the people and the places we love goes on and on like an endless loop. In some lives, you come close; in others, you don’t.

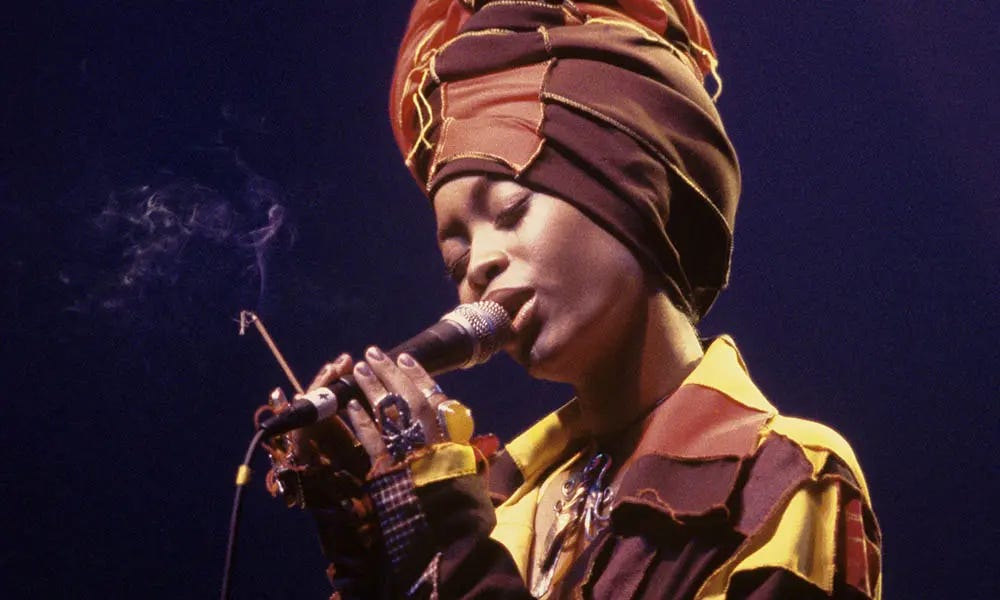

This sentiment is echoed in Erykah Badu’s Next Lifetime where she narrates meeting someone who could be her soulmate while committed to someone else. This scenario would emotionally wreck the majority of folks but for Badu, who has always been immensely spiritual, with references to fate, astrology and astronomy in her songwriting, the decision is a casual one. She tosses it up to fate, to in-yun, on this track off of her GRAMMY-winning debut, Baduizm:

Now what am I supposed to do / When I want you in my world / But how can I want you for myself / When I'm already someone's girl? / I guess I'll see you next lifetime.

Both Celine Song and Erkyah Badu, two artists of different backgrounds and different eras, pull from separate theologies that reach the same conclusion. All these hidden nodes and invisible strings are secretly at work, tying us and the things we love together. Perhaps, the two could have been in conversation, potential collaborators at a writers workshop, even lovers, in a past life.