Did you know that there is a secret garden, secluded and derelict, on the northeastern crest of Brooklyn’s Prospect Park? Roughly 17,000 years ago, a glacier melted and carved into the earth the natural topography of what would become North America. As the ice sheets thawed, a divot formed somewhere in present-day Brooklyn. At the close of the 1800s, this uncanny terrain inspired the designers of Prospect Park to construct a garden around the divot named the Vale of Cashmere, dense with sweeping woodlands, verdant beeches, rare Egyptian lotus and water lilies that sunbathed in cerulean pools. By the early 1900s, if the weather was bearable, families found themselves sprawled out on the lush landscape with club sandwiches and iced beverages. Children frolicked in the fountains, their joyous shrieks cradled by the wind against the chirps and chatter of the birds who had made a home of the garden. At the time, all was well.

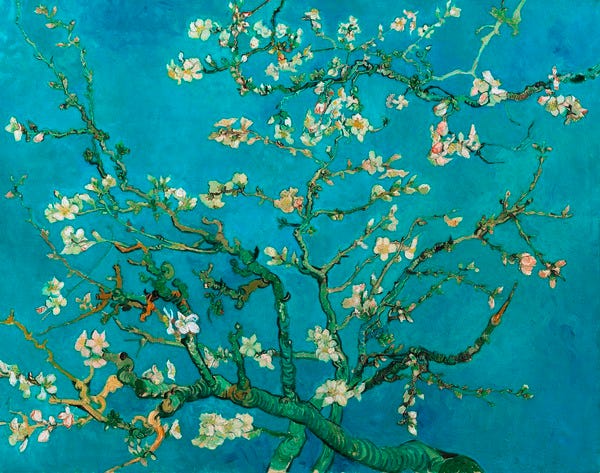

Over the next century, the city lost funding to preserve the park. The fountain pipes burst, never to be repaired, and the pool that once kept waterlilies afloat became overflooded. With the garden’s decline, the families disappeared and, in their place, the Vale of Cashmere ushered in a new crowd. Tainted by crime, suicide and cruising, the Eden of Prospect Park became polluted and dilapidated. Its apple had been bitten and left to rot. As virtue escaped the woodland, so did the flourishing terrain as its exotic fauna overgrew with mossy shrubs and its palatial fountains ran bone dry from neglect. Today, there is no praise for the Vale of Cashmere. There is no reward given to a garden that was once beautiful. Other than you and I, no one seems to know anything about the vale. It’s forgotten. It’s overlooked. The flowers we once gave the secret garden have now died.

Time can be a trickster, skewing our relationship with recognition and reward like a funhouse mirror. For the better part of a decade, Girls has been a polarizing time capsule of the early 2010s, generating equally passionate degrees of praise and hatred. My capacity for reserving a place in my heart for messy Geminis who consistently orient themselves at the center of controversy (Azealia, Prince, Lana [reformed], Angelina, etc) knows no limits. I find myself overlooking their surrounding discourse for the sake of their art being so damn good. This has absolutely nothing to do with Lena Dunham, the creator of Girls. As Dunham is a Taurus, I am incapable of drawing a correlation between her star sign, the art she produces and her commentary, the latter of which tending to provoke public outrage followed by a subsequent apology on her behalf. But like most storytellers, her characters and storylines are informed by her own identity and experiences. Her art is intrinsically tied to who she is. To demand that Dunham or any of the above artists alter their perspective to adhere to the ever-changing politics of the present would be to indirectly shift the direction of their creative output. If they were to become ‘less messy’ as people and ‘more palatable,’ it could also be assumed that they would lose the very fiber of what makes their work so special.

To criticize Girls is to criticize Dunham herself. If fact, if I were to construct a Venn diagram of those who dislike the show and dislike the show’s creator, I would likely find that I am able to squeeze the majority of detractors into the skinny, sliver of an oval wedged between the cleavage of the two bigger circles. Upon its original airdate, the criticism of Girls circled around takes that the characters were too annoying, that it was not an accurate portrayal of New York, that it was too white, that it was too fat, that it was too cringe. Despite this, Dunham defends that this was all by design, that Girls is not meant to be an honest depiction of four young women in New York but a satirical one. In a CBC interview, Dunham confirms that Girls is “a commentary on what it means to be a white middle-class person but I think people made the assumption that we were far less aware of what we were doing.” And yet, over a decade later, perhaps sparked by fandom over Allison Williams in M3GAN, critics and fans have all returned for The Great Rewatch. This year, we collectively cringe at the clunky sex scenes between Hannah and Adam and unilaterally laud the “Beach House” episode of season 3 with unabashed praise. It is only now that we recognize that no one is ‘a Hannah’ or ‘a Marnie’ or ‘a Shoshanna’ or ‘a Jessa.’ Instead, we are all Rays, the only character tethered to reality and simultaneously exhausted by it. Upon rewatch, we admire the glimpses of humanity Dunham etched into her characters and shudder at the parts we find familiar. As we laugh a little bit harder at the jokes we first heard a decade ago, it appears that there are more lovers of the show than haters the second time around. It appears that viewers are finally able to separate Dunham from her art and come out enjoying the latter regardless of their opinion of the former. Perhaps, Dunham was in on the joke all along.

What does it say about our palates if it takes almost a decade to metabolize art? For the majority to finally give Dunham her flowers, did a shift in our politics have to occur or did the steady stream of post-Girls programming such as Insecure and Broad City, and maybe even Chewing Gum and Fleabag, make it easier to enjoy the once-considered outlandish genesis? Nina Simone elicited that “an artist’s duty is to reflect times” but what happens when, instead, an artist captures the future? Does that make the artist a genius or does that make them terrible at producing art?

Perhaps, it makes them a visionary for pushing the culture forward with the hopes that our politics and tastes will eventually catch up. Maybe some things do get better with time. Or maybe they don’t. We do.

When it comes to music, we experience the effect time has on our sensibilities the most when returning to albums of the past. I am of the mindset that a perfectly engineered album should feel timeless and urgent in any year that it’s encountered. Originally released in 1971, Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On uniformly conjures this sentiment. Although Gaye’s production sonically matches the soulful timbre of the seventies, the content of the tracklist outlives the decade. Erupting as a plea against violence, police brutality and civil unrest, What’s Going On was unfortunately prescient. It operated as a beacon to lead listeners out of the injustices of the seventies only to continue to foreshadow the turbulent times ahead in many parts of the world. Similar to Dunham’s Girls, the work’s merit and praise continue to compound as years pass. A key difference between the two is that the recent praise for Dunham’s magnum opus signals how much our politics have progressed while Gaye’s continuous credit serves as a reminder of how much our politics have not.

When praise finally catches up to the demands for representation, it’s difficult to isolate the triumph from the time elapsed to get there. Upon witnessing Michelle Yeoh and Ke Huy Quan receive their respective Oscars for their multifaceted performances in Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022), I studied their faces for vitriol. I closely eyed the lines of their smile for the thinly fleshed indentation that resembles not a grin but a snarl. My ears Shazamed the intonation of their voice during their acceptance speech as if to hunt for disdain. To finally receive praise in front of a room that is representative of the very system that held you back, a system that pigeonholed you into a type-casted box, is a fantastic opportunity for revenge. A perfect layup to a well-overdue tongue-lashing. And yet, on that stage, lips to the microphone and golden statue in hand, all I was able to locate was grace. Gratefulness and appreciation to finally receive credit where credit was overdue. But then I remembered that they are actors. Academy Award-winning actors.

I often try to imagine a world that is perfect. That is, I envision a world where Beyoncé rightfully has won three GRAMMYs for Album of The Year (Beyoncé in 2015, Lemonade in 2017 and Renaissance in 2023, respectfully). Then, I remember the world I live in, the world that inspired Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On and, instead, I try to imagine how Beyoncé might feel when she finally wins an AOTY award. I find it challenging to believe this achievement would feel redemptive at this stage of her career. As the recognition is materially overdue, I would imagine that the emotions harboured by the most GRAMMY-winning artist would be a maelstrom of gratitude, resentment and embarrassment. I’d expect this ying-yanged response to extend to some of the most ‘overdue’ actresses in relation to the Academy Awards: for Bassett, for Adams, for Close, for Woodard. To be applauded whilst receiving withered flowers is both bittersweet and corny. In 1996, when Marvin Gaye finally received his Life Time Achievement award at the GRAMMYs, he was already dead. There is a point where accolades cannot make up for lost time. What good are flowers if you can no longer smell them?

In the next year or so, the Vale of Cashmere will finally get its flowers. Brand, spanking new flowers at the price tag of $40 million funded through a revitalization project from the city. In exchange for its patience, the renovated Vale of Cashmere will gain an amphitheatre, a community center as well as a fully restored children’s pool. The revival of the park indicates that a paradise lost can be found again. It posits that with a new set of flowers, no matter how delayed, recognition can sprout in place of neglect. But what if we bought ourselves flowers, instead? What if, instead of waiting for flowers from some self-appointed power, we gave them to each other and tended to the garden within ourselves? I do not have $40 million in the bank yet but I have enough to buy myself some peonies. I certainly have the coin to bring you calla lilies to rest patiently on your window sill. Spring is finally here. Wouldn’t you rather smell the roses than wait around to push up daisies?